I wrote for two months straight.

I wrote an essay about Surrealism, the perception of time in 19th century England, gender binaries in the kitchen and a dissertation about trauma’s impact on masculinity. I have laughed and cried, been brought to my limits and back, but I did it. After three years of uni, I finished my degree.

In these two months, I had no creative outlet. Some would argue that academic essays are creative in their own right, but I always struggled with that. Creativity is authenticity, and I am not authentic in academic essays.

I have to pretend to speak in a certain way about a topic on which I would normally not write an essay on. In academic writing there is no room for unprofessionalism, quirks or uncertainty. Everything needs to look the same and sound the same. There are rules to follow, and if you break them, you will be penalised.

I always saw it as a performance. Nothing more than a vehicle to transport an idea. The delivery van of writing. I had spent so many late nights of my life in the library, nights came where I questioned why I was doing all of this.

Was this all a shallow performance or was there more behind torturing myself everyday in the library?

So now, after one of the most stressful periods of my life, on vacation in Spain, I want to take a look back at my academic writing career to really understand what benefits academic writing had for me.

At points this may read like a writing guide, but given the fact that I am only now figuring out what writing is, take everything I say with a grain of salt. Although, of course, I am an incredible writer.

Analytical Structure:

One thing I always liked about academic writing is the end product. There is just something so satisfying about seeing everything that I have worked so hard for come together into a neat argument.

I get the same feeling looking back on my past posts on Substack: a little, clear essay that I tried to lay out, and that people can follow. I found that it’s this ability to follow an argument which makes it worth reading. And to achieve this it needs structure. Something that becomes painfully obvious when i look back at my old essays.

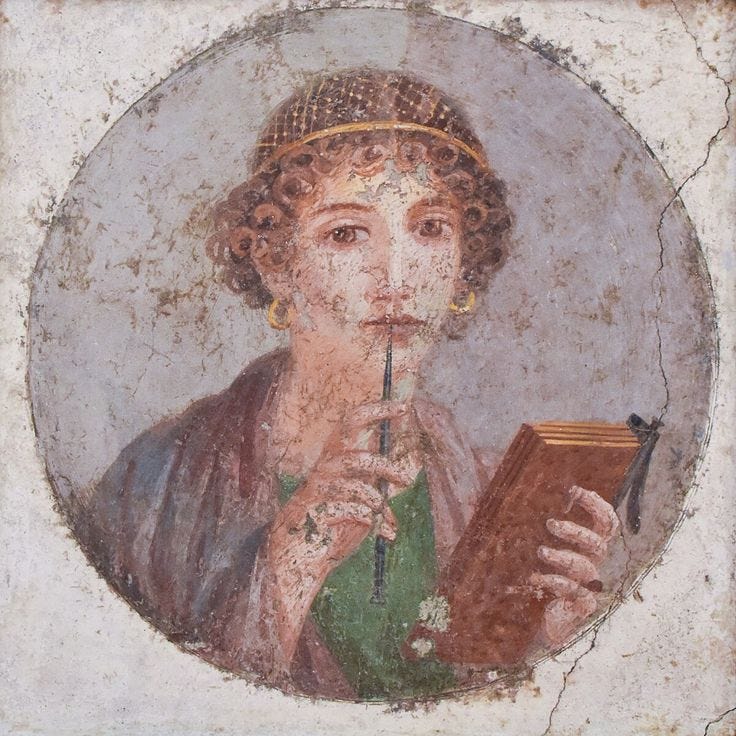

In the metaphorical attic of our submission portal, I found the first essay I ever wrote, catching digital dust. It was about Sappho and the gaps in her poetry, and I remember that, when presented with the task of writing it, I was excited, confident even.

I got a 60. It would have been much worse if our examiner at the time had not been aware that there were a lot of students that had never written an academic essay before. Indeed, she left encouraging feedback:

This is a promising essay that uses a good range of examples to answer the question, demonstrating independent research, and while it lacked signposting it did have structure. Its two main weaknesses were that it did on occasion veer towards the descriptive rather than the analytical and also that it did not cite any of Sappho's poetry.

Well, not citing any of Sappho’s poetry is bad, that’s for sure, but what was that word? Signposting?

A memory came to mind. My lecturer in the seminar talking to us: “Always introduce what you write about before you write about it.” I made a mental note: A structure is nothing if people can’t follow it.

That doesn’t even mean that I have to signpost. If I am able to take the reader by the hand, signposting might be more disruptive than helpful, but it depends on what I am writing. A piece on Substack will read differently than my dissertation.

Here, my lecturer’s second criticism came into light: if I write an argument, no matter the topic, I need to go deep and make the reader understand.

This requires what I call an ‘analytical structure’, which is a structure that allows for deep exploration into a topic, giving space to each point. An argument needs to be understood, stripped bare and laid out. Only then am I able to put it into writing and only then is what I write interesting to read. Otherwise, I am just summarising readings.

A good way I found to approach this is to assume that I have the smartest reader on the planet but that they are both easily confused and not knowledgeable. If anyone that doesn’t know anything about my topic can understand what I am writing about, I did my job.

As Einstein said: “If you can’t explain it to a six-year-old, you don’t understand it yourself.”

Formatting:

In my lecturer’s feedback, she continues:

A further aspect that requires some reworking is presentation, especially your paragraph breaks. One paragraph = one point in your argument. The breaks are where you transition to the next point. Having multiple breaks when you are just talking about one point is disruptive to the reader. Also, we never use single-sentence paragraphs in academic writing: that is a literary device.

She couldn’t have put it better. Especially the last sentence hit home for me. At that point I had discovered fiction writing for myself and would insert paragraph breaks after every sentence. Let me tell you: if you need a paragraph to tell you that something is important, your writing is shit. Academic or fiction.

This was the first time I understood that the format is as important as the content, because the content will only be read if it passes the biggest hurdle: the first impression.

It’s a way to see how serious you are about your writing. If you are, then the ten minutes to make it look professional show that. Why should anyone read what I wrote if I myself don’t care about it enough to make it look nice?

This begins at the very basics of formatting (12pt, Times New Roman, double-spaced) and goes all the way to the intricate footnote guides that I have to consider when hunched over in the library until 4am on a Monday night.

The same applies to fiction writing. Most magazines want you to submit after Shunn’s manuscript guide. Here, academic writing has made me appreciate the beauty of sticking to a format and being consistent with it. Applying proper formatting is something I now almost enjoy as much as the writing itself (insane, I know).

Style:

After formatting, I can then concentrate on the style of writing.

Of course, fiction writing allows for a much broader range of styles but nonetheless, there are still some general rules that I follow for both academic and fiction.

An example of this would be adverbs. In the beginning of third year, my film lecturer, explaining how he wanted us to write his essays, quoted Stephen King: “The road to hell is paved with adverbs.”

It’s not that adverbs are unimportant or useless, just that you should only use them if you really need to.1 There is no point in saying, “This fully encompasses”, because from everything I have said, it should be understandable that it fully encompasses it.

Same with writing fiction. No point in saying “She said nervously”, because the context should already make it clear she’s nervous. Sticking to simple rules like this will make the content so much more engaging for the reader, I found.

Of course, everyone will develop their own style when it comes to writing. I have friends who love to use semicolons, and long sentences, which they make work. And I have friends who write almost colloquially but still in an academic tone. Yet, simple rules like these are what elevates writing from any style and level.

Research:

When speaking strictly of academic content, research is probably the most important part to consider. Which makes sense. I mean, an academic essay is always an exploration into a topic, through research and original thought.

I did not know how to do that. Original research sounded good to me but what I ended up doing was just searching my topic in Google Scholar and citing almost every article I could find. Not only did I use way too many scholars for what I was writing, but there was no depth to the use of them.

If, for example, a scholar referred to Don Quixote as a novel, I would quote them, when doing the same. I did not care that it wasn’t them who made that original assessment or that in fact you can just say some things without having to provide a reference (I don’t need a scholar to tell me the sky is blue).

After being told by my lecturers and girlfriend that I would need to go deeper into my readings to justify the use of certain scholars, I tried something new.

I went through the citations of the readings, and I looked up and read the ones I saw cited repeatedly. It’s a quick and, as my dissertation supervisor put it, ‘dirty’ way to find the foundational texts on your topic and let me tell you it changed a lot.

Turns out knowing what articles are talking about is actually a good way of understanding what you are writing about.

It also helped me gain confidence in asserting my position as the more I read about the topic, the more confident I became–and that, I think, is what all of this has led up to.

Confidence:

Today, as I’m writing this (4.6.2025, at 8:42 am), I will receive the grade for the dissertation that I have been working on for a year.

I’m nervous of course and will be disappointed if I get a bad grade. But no matter what, I’m grateful for what all of this work has taught me. It’s not the formatting, style or research, I have such an appreciation for (even though of course that has helped me become a better writer).

No, it is that I have found confidence in writing.

My academic essays and the invaluable feedback I have gotten over the last years (far too much to include in this post) have made me confident in arguing what I believe in.

Without that I would have never felt adequate enough to express my opinions (especially not in my 2nd language) on this platform.

For that I am grateful, even if this little post felt a bit tedious to get through and reads more like a writing guide from someone who still tries to figure out what writing is.

I needed to write this little post to get both back into writing and to bring my academic career to a metaphorical close (at least for the foreseeable future).

So what do you guys think? What have you learned from academic writing or writing in general? Always interested to know what my wonderful reader’s perspective is on these kind of topics. What are your experiences with academia in general? Hate it? Love it? Am I chatting bullshit? Leave me a comment and let me know.

I, for now, can’t wait to dedicate the next two months to writing and pick this Substack thing back up again. Now with more confidence than ever.2

I know most people know what adverbs are but on the off chance you don’t—like me when I first came across the term again more than a decade after learning the basics of grammar in primary school—every word that describes how something does an action and ends with an -ly, is an adverb.

For those that made it to the end, I did get my dissertation grade on a sunny beach. I got an 82. I was speechless.

Sehr stark bro. Und interessanter post