How London's Free Museums Keep Us Alive

What Ben Stiller has to do with colonialism and community

The London Natural History Museum is beautiful.

Red bricks, gothic architecture, and small columns that remind you of palm tree trunks. The two towers you see from the main entrance stand grandiose and tall, with pointed metal poles on top, making you think of Frankenstein’s manor; lightning could strike at any moment and generate enough power for the mad scientist who might live there.

After getting over your initial awe, you go inside and are welcomed by the real monster of the house. No, not a monster. You look again. The blue whale skeleton is hanging from the flower-painted ceiling, mouth agape, inviting you into this magical place.

You feel like a kid again and ask your girlfriend to take a picture of you in front of it. Then you realise that, for this one-of-a-kind experience, you paid nothing.

This is what happened to me on Saturday.

While walking through the museum, I kept thinking about it.

As a German, I was shocked.

In Germany, you still have to pay for museums. The same is true in every other country I have been to—France, Spain, Italy, Austria, Denmark, Iran.

Enjoying the beautifully curated exhibitions, I thought: “Why?”

Why did I ever have to pay for a museum? Shouldn’t this be the golden standard? How can it be that in one of the most expensive cities in the world, every museum—from the Tate Modern to the V&A—is free, while you have to pay thirty dollars at the Met or twenty euros at the Louvre?

Interested, I Googled it and found an answer that leads us—as much as I hate to say it—to Tony Blair.

In 1997, the Labour government implemented a policy which stated that all government funded museums would not charge an entrance fee. This led to an 150% increase in visitors over the next 10 years.

Everyone enjoyed art, and everyone profited. Museums got money from the government; people could go for free. Quid pro quo.

What is this article about, then?

It’s prompted by another article I found, which asked if keeping museums free was feasible.

Since 2009, government spending on museums has decreased by almost 37%, while museum staff earn on average less than thirty thousand pounds per year. The article suggested that all of this could be solved by charging visitors around five pounds.

Another piece in The Guardian advocates returning to the old system—saying that charging fees is the only way to save museums, and that Spain and France have been doing it the entire time.

My initial thought was, “Well, maybe Spain and France should do the same as the UK, not the other way around.”

I mean, having free museums is incredible.

Since moving to London, I have been visiting them all the time. Not only can you go when you have an hour to kill, but you also never have to worry about money when planning your Saturday: just go into the National Gallery and look at art for free. When friends are in town, I always suggest going because it is a no-risk activity. If they don’t like the exhibition, we just leave—no loss of money, no strings attached. And, if they do like it, there’s always a lot to learn—surrealism, dinosaurs, geology, Irish history, German history, evolution, insects. Easy access to education, all because you don’t have to pay an entry fee.

Otherwise, you wouldn’t go. Sure, culture is nice but having to pay forces you to think about whether it’s worth it or not. Once you’ve paid, you feel compelled to spend at least a couple of hours there, or else you’re wasting money. You wouldn’t be able to walk past a museum and ask your friend, “Have you ever seen a Monet painting up close? Do you want to?” and then continue with your day afterwards. That’s why my girlfriend and I went to the Natural History Museum in the first place. She asked if I wanted to go, and I said yes—no strings attached.

I realised that there are almost no spaces left where you can simply exist without spending money. These third spaces, between home and work, make life liveable and enjoyable, yet they are increasingly hidden behind paywalls. You cannot sit in a café without buying coffee—but in London, you can still walk into a museum and not pay an admission fee. This leads me to Ben Stiller.

That same night, after our visit, imbued by the spirits of dinosaur skeletons and taxidermized mammals, we decided to watch Night at the Museum. For anyone not familiar with the movie (I am deeply sorry about your failed childhood), I will summarise it quickly.

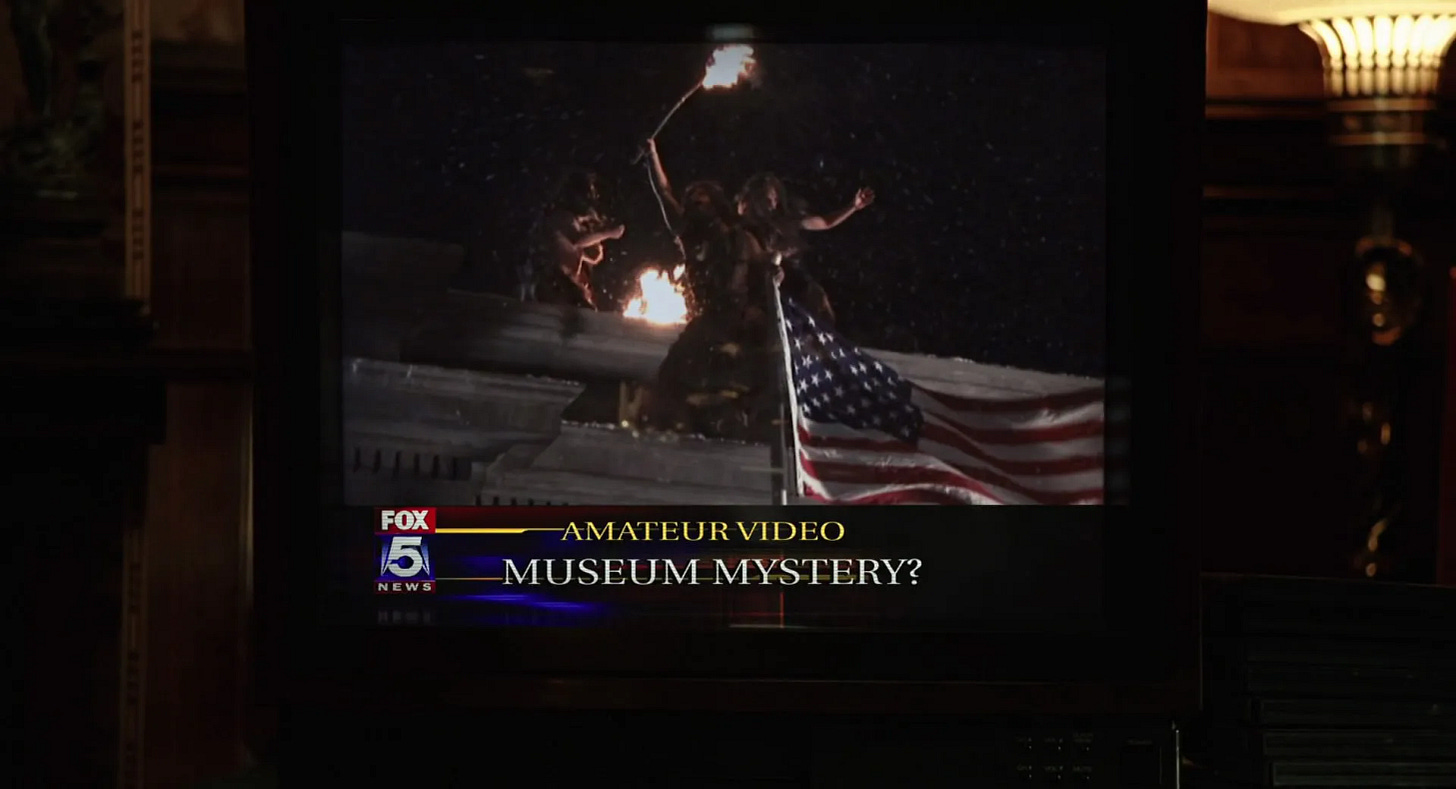

Ben Stiller is a down-on-his-luck divorced dad who takes a job as a night guard at the Natural History Museum. On his first shift, everything in the museum comes alive at night. The reason? An Egyptian gold plate that has been with the museum since the 1950s and possesses magical powers. Amusing chaos ensues, and Stiller fails to keep order, leading the museum director to fire him. Begging for one more chance, he returns and—with help from the museum’s exhibits—stops a robbery planned by the previous night guards. In the end, the museum is saved, though chaos is now all over town—from giant T-Rex footprints in the snow to cavemen on flagpoles. The director fires Stiller again but rehires him when he realises the public spectacle has brought in more visitors.

Why did I summarise the whole movie? Well, one thing is certain: the movie couldn’t have taken place in England. The entire reason Stiller’s character gets that job is that the museum is downsizing due to a lack of visitors and, therefore, a lack of funds. In fact, profit is the most important thing for the museum.

The museum director is more like a businessman running a company than a cultural attaché; keeping the board happy and making money is the only thing he cares about. That’s why he only reinstates Stiller after he brings in more visitors—and also why he replaces the three old night guards in the first place.

The museum in the movie is thus denied becoming a dedicated third space for the community, as it is driven by profit. The only “community” you see in the movie is the schoolchildren who visit on a class trip. If the school didn’t pay for them, the kids wouldn’t be able to go.

But if you go to the Natural History Museum on a Saturday, you’ll see more children running around with their families than on any given weekday. That is possible because admission in the UK is free. As poverty in this country rises (in 2024, 21% of people were below the poverty line), the museum remains one of the few places where children can feel part of a community. It doesn’t matter what your socioeconomic background is; only that you love dinosaurs. Kids can be kids and learn about art and history. This idea appears in Night at the Museum, where kids mainly learn about American history.

Thus, at night, Civil War figurines, Manifest Destiny cowboys, Lewis and Clark, Sacagawea, and Teddy Roosevelt all come to life. As the movie explains, the reason for that is the magical powers of the Egyptian plate. We learn that the plate was initially brought back to England and then taken to America. In Night at the Museum, thus, the products of colonial conquest keep the American project and its remembrance literally and metaphorically alive.

I know what you are thinking.

“It’s not that deep, bro. This is a movie made for children.”

And I agree. You might even wonder how you ended up reading a neocolonial reading of a Ben Stiller film. I don’t blame you. Let me explain.

Many museums, such as the British Museum, are rooted in the imperial core—stealing artifacts from other countries and now ignoring requests to return them. That’s often how museums operate, and I’m not condoning it.

Still, much like in Night at The Museum, the artifacts in museums do, in a sense, keep us alive. London’s museums, in particular, are among the last bastions of genuine public community.

Yes, colonial spirits haunt some of them, but stolen artifacts are not necessary for a communal spirit. The Tate Modern, for example—focusing on modern art—is a great example of a free, non-colonial museum.

I got to know my friends and girlfriend better by going to these museums, and I learned a lot about myself and the world. This would not have been possible had I needed to pay for every visit. The museum was a third space par excellence that I, in a sense, needed to stay alive.

We are truly alive only when we can wander around a museum and enjoy art without rushing, worried about having paid twenty pounds for a ticket while the museum closes in an hour. The same applies to other third spaces. You feel alive reading a book in the park or studying in a public library (depending on your relationship with academia). Here, Night at the Museum made me see us almost as artifacts of capitalism, kept alive by these third spaces.

The answer to the Guardian article thus seems simple: museums should stay free. But how do we pay for it?

The same way we could solve every major social issue, from housing to food prices: taxation.

Increasing capital gains, dividend, estate, and inheritance taxes would benefit everyone and allow the government to boost subsidies—paying museum staff liveable wages and preserving community in an ever more individualistic society. Teddy Roosevelt agreed with that. And if he can be brought to life by the spirit of a museum, so can we.

An meinen lieben Neffen,

dein Artikel über Museen hat mich so berührt, dass ich während meines München-Urlaubs direkt ins Deutsche Museum gegangen bin, genau wie damals, als du, dein Bruder und meine Tochter wie kleine Abenteurer durch die Hallen getobt seid! Erinnerst du dich? Ihr habt gelacht, Fragen gestellt und euch an den alten Flugzeugen festgehalten, als wären sie Drachen.

Dieses Mal stand ich zwischen Raketen und Robotern und dachte ständig an euch. An deine klugen Worte: dass Museen Menschen verbinden, dass sie Freude schenken und Neugier wecken – und du hast so recht!

Ich sah Kinder, die sich ohne Handys gegenseitig die Planeten erklärten, Jugendliche, die lachend über Chemie-Experimente diskutierten. Genau das, was du auch in deinem Schreiben beschreibst.

Museen sind Orte, an denen Wissen nicht einsam macht, sondern Gemeinschaft schafft.

Und weißt du, was mir klar wurde? Du bist nicht nur ein toller Schreiber, sondern auch ein Visionär.

Dass Museen kostenlos sein sollen? „Ja!“

Denn jedes Kind sollte dieses Wissen erleben dürfen, so wie neulich im Museum, als drei Kinder ihre Hände auf die Planeten Erde legten und plötzlich ein Team waren und sich darüber unterhielten.

Danke, dass du mich daran erinnerst, wie wichtig es ist, Räume zu schützen, in denen wir staunen, lernen und einfach zusammen sein können.

Mach weiter so, deine Stimme ist wichtig. Und wenn du das nächste Mal schreibst, denk daran: Irgendwo rennt gerade ein Kind durch ein Museum und fühlt sich genau so heldenhaft wie ihr drei damals.

In Museum gab’s eine riesige Glaskugel voller Blitze, da wollte ich dich direkt anrufen und sagen: „Sieh mal Kian, das ist genau das, was deine Worte in mir auslösen:

„Funken!“

Von der Ausstellung über Gutenbergs Presse habe mir einen Satz für dich abfotografiert, den ich dir mitgeben muss: „Jeder Buchstabe ist ein Samenkorn für Ewigkeit.“

Schreib weiter, als würdest du Wälder pflanzen.

Ganz viel Liebe und Stolz,

Deine Tante Laila

museums, libraries and parks; the best parts of a truly great city